Once again, America is burning.

My eyes were lately most on Hong Kong, where I have some dear friends, where their protests have become increasingly violent.

And then yesterday it happened here, in Minneapolis as a reaction to the police’s murder of George Floyd. It spilled over to my home in Los Angeles, where downtown protestors spilled onto the freeway. If you have to even ask why in LA we always join in when there is police brutality discussion, you probably forgot 1992. Your probably don’t remember the reputation of the LAPD. You probably don’t fully get why “Cop Killer” came out of our city—that song was written in 1990, before the LA Riots, many seem to forget.

I was 14 in 1992. I remember that morning so well, the morning after we all saw the Rodney King beating on our televisions. This was obviously before smart phones so the fact that it was recorded felt like a miracle, even though what it captured felt like no surprise to me even at 14. I had already been warned by relatives that the police were very dangerous—that they raped women, that they assaulted men. I remember an elder telling me once I drive that if a cop chases me on a highway to just keep going—better to be in a high-speed chase than pulled over and raped. I was terrified of police at a young age and so when I saw the blurry green and black tape of Rodney King’s beating I did not cry. I was just angry. I knew somehow that this happened all the time and that my community was doing nothing about it. I watched my parent’s silent tense discomfort as as ate our dinner in front of that television. We had only been in America a decade and none of us, except my nine-year old brother, were citizens. This land was not our land. And yet immediately I heard my parents compare it to the the revolution era in Iran and their brutal police and the awful beatings my relatives endured in prisons.

I went to school that day and by lunch time, you could smell the smoke in the air and see bits of ash. Pasadena is just over 10 miles from Downtown LA. I often walked home from school but by seventh period the teacher passed me a slip saying my mom was coming home early from work and that she would pick me up. Play practice was cancelled. By the last class of the day, social studies, our teacher had no choice but to bring it up. “I think we need to talk about how awful it is that people are burning down their own neighborhoods. This is unacceptable,” the white woman said, with her voice shaking. She was probably my age now. I raised my hand. “I think it makes sense,” I said. “I think we need to think about why this happened and not blaming the people in the street but blame what caused it." My teacher looked shocked—I wasn’t one to speak up in that class. Everyone shuffled in their seats. “What do you think caused it?” she asked me. “Racism,” I said. I remember once I had begun to talk I could not stop and that when she asked me to go to the principal’s office, that this was not the time for divisive talk, that the tears in my eyes that felt so hot also felt so old and familiar. I walked to the principal’s office and paused at the door and kept walking, toward home, until my mother’s old Honda hatchback pulled up by the curb just a few blocks from our apartment district. She told me why was I walking, did they not tell me she was coming, and that it was no longer safe to walk. I got in and watched her windshield wiper wipe ash from the window. When we got home, I sat glued to the television. “They are very mad,” my mother said nervously. “We are very mad,” I remember mumbling back.

When the OJ Simpson trial happened just a few years later and we all watched Mark Fuhrman take his oath, we did not think first about the football celebrity or the slaughter of his wife and her lover. We thought about the LAPD and how there was no more dangerous entity than them. When OJ got off, we saw it as a victory against the LAPD, not that a rich powerful man—a black man— had actually killed two white people and got away with it.

Another year after that I was in New York for college. At 18 I already knew the spots where they would not card in the East Village and getting drunk at cheap happy hours well into the night was our pastime. One time after a long night out my friend and I, very drunk, realized we ran out of money and so we jumped the turnstile at the Astor Place Number 6 station. On the other side, was a cop. My friend quickly apologized as the cops wrote her up while I flipped out, in my drunken haze swearing obscenity after obscenity at the cop. My friend kept yelling that you can’t yell at cops, that you could get arrested, shut up, while the cop wrote me up with a smile. I was no threat, he knew that. It had not occurred to me that vocally hating on cops was not allowed. I tried to explain to my friend later on the train that where I grew up “Cop Killer” was on the radio, that these people were our enemies. My friend never went out with me again.

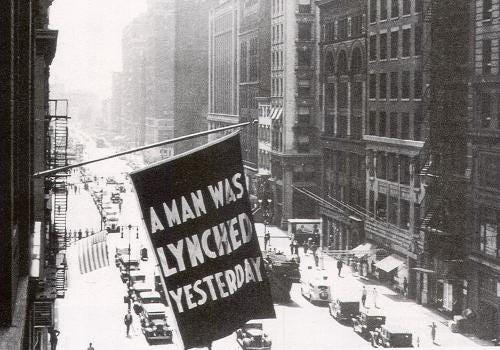

A few decades letter on the eve of the Ferguson protests, where on Twitter we sit awaiting the verdict, it comes and there is no surprise. I take my dog out on a walk, crying silently as I hear one of my older neighbors in Harlem play “Strange Fruit” on loop out his window, the only sound you could hear that mostly silent night, echoing across Marcus Garvey Park.

Around that time, I taught a nonfiction workshop at Wesleyan. Long drives back and forth, a Metro-North train from Harlem 125th to New Haven station and then a zip-car to Middletown. At the New Haven station the black poverty was always a shock to me, this so-called illustrious city that houses Yale. I could never shake off its mood even when I’d walk into that quaint cottage where my office was, flanked by beautiful trees and flowers. Around that time, I taught Thoreau’s “Plea for Captain John Brown” for the last time. Thoreau had delivered this speech just two week’s after the raid at Harper’s Ferry in 1859 and again many times up until the radical abolitionist John Brown’s execution that same year. This is the speech where we got “The question is not about the weapon, but the spirit in which you use it” and less famously,

“Only half a dozen or so have died since the world began. Do you think that you are going to die, sir? No! there's no hope of you. You haven't got your lesson yet. You've got to stay after school. We make a needless ado about capital punishment- taking lives, when there is no life to take. Memento mori! We don't understand that sublime sentence which some worthy got sculptured on his gravestone once. We've interpreted it in a grovelling and snivelling sense; we've wholly forgotten how to die. But be sure you do die nevertheless. Do your work, and finish it. If you know how to begin, you will know when to end.These men, in teaching us how to die, have at the same time taught us how to live.”

How do you teach this in an America that still looks like this over a century and a half later?

On November 25, 2014 at 11:18am I got this email from a Latinx student in that Wesleyan class of mine,

“Hi Prof,

I am needing our class and the space it provides for me today. I am desperately craving it. I don't want normal today. It does not feel right to continue on today like nothing happened last night. Like the symbolic and real life consequences of the nonindictment of wilson are not significant. I was in class last night while the live stream in Fergusonwas happening and I just had to bring it up, in this class where I was 1 of 2 people of color present. I broke down, and I didn't mean to have such an emotional response because I knew he was not going to be indicted. We have seen this narrative over and over again, before and even after Michael Brown. Our pain has been continuous. I felt so stupid, and powerless, for crying in class because I knew my peers didn't get it. They didn't understand why this was so important to me and why it was affecting me in such a way. We had our moment of silence in solidarity with Ferguson and Mike's family after the decision was made public. Moments after my peers were laughing and joking about something else again. Back to normal. I had to leave the class. It was not a supportive environment for me. Today I dread going to class because it will be just another regular day for most of my peers. These are people that had a nice, restful sleep last night. They woke up this morning not having to think about Ferguson or the decision last night and its daily manifestations in our everyday lives. And that is unsettling to me. I am heart broken and devastated not only for Michael Brown and his family; I cannot begin to imagine the pain they have had to live with. This goes beyond Michael Brown. I cannot be complacent in normalcy today because this decision means that my little brother's life does not matter. It means that my future son's life will not matter. I don't want normal today, but I am also feeling hopeless because I know dialogue won't happen how I envision it. I am terrified to delve too deep into and discover the great depth of white privilege and ignorance. I don't want normal today but I also don't want to have to defend black humanity. I am tired of defending my pain and anger, because these personal and valid feelings are not valued in these academic spaces, they are seen as unproductive. But all I want to do is scream and cry and burn everything to the ground.

All of this is just to say that I appreciate you, and our class. I appreciate you because you do not act like we live in a bubble separate from the "real" world that is "outside" of us. We cannot distance ourselves from these issues. That, and not my tears, is what truly is unproductive.

I hope you have a restful break and hope you are given the chance to process this in a supportive environment. Here's hoping I don't have to destroy anyone in my intro to soc class later because today, I am not having it. I'm channeling my inner Audre Lorde. Today I will be deliberate and afraid of nothing.”

I think of that email all the time and I wonder where she is and what she is doing today.

Today, I am thinking of her and I am thinking of my younger self coming of age in LA Riots LA. I am thinking of young people watching and deciding what sort of person they want to be. I am thinking of older people still amidst this decision. I am thinking of fear, in all its forms, and what it does to us. I am thinking of Minnesota: the footage we saw of Minneapolis reminds me a lot of the aftermath of the Riots—an eerie stillness, smoke still in the air, the sleepless still walking the streets where everything is closed and will be for some time. I am thinking also of our brothers and sisters in Hong Kong and the demise of their home. I am thinking how even in a pandemic so many forms of fascism can still thrive. Protests are long in my blood—my father would remind me many of my ancestors were known only as “warriors,” no other vocation to speak of—and I know their purpose. They are a reaction. People fear their violence but they forget to fear the violence that sparked them in the first place. May our protests bring us closer to justice and freedom, as long as we still have time.